You can listen to the essay below.

Dear Friends,

Greetings in these early December days as the light continues to lessen and we slowly make our way towards the shortest day of the Winter Solstice.

Before I share my new essay, “What Remains: On Quilts and Grandmothers,” about the moments of synchronicity and illumination in our everyday lives, I want to mention that I’ve been having a great time reaching out to my friends and contacts in Ireland to organize our next writing retreat and tour for September 2024. How wonderful to hear those lyrical Irish accents! After these recent years when there were times I had no idea if I would ever be able to offer such a tour again, it is thrilling to know we will be there in that magical landscape soon. Keep an eye out for a formal announcement next month.

Please note below a few recent recommendations of films and reading, as well as details about submissions for the April 2024 “In Celebration of the Muse” poetry reading in Santa Cruz, sponsored this year by the Hive Poetry Collective. I also invite you to share this newsletter with those who would be interested.

Blessings to you as we all allow the darkness to teach and reveal what is hidden and quiet, what is growing on its own in the fecund soul of the earth, and in our hearts and inner sensing. I know these times can be scary and hard. We are here in this community and this world together, to hold each other up. As my friend and teacher Deena Metzger writes, “Be and provide sanctuary.” This we do for each other.

All my love,

Carolyn

What Remains: On Quilts and Grandmothers

The quilt in my hands was lovely, stitched in a pattern of small baskets on white cotton. It was old, very old, and hand-sewn, every quilted stitch, each so tiny as to be almost invisible. The teal and navy blue baskets had been carefully cut and sewed onto creamy white cloth, thirteen to a row, twelve rows, stitch upon stitch upon stitch. The quilt was now one thing but it had once been many things: an old dress, a worn blouse, an apron or a nightgown, and before that spools of thread woven into fabric, and before that puffy white cotton on a twig—things becoming things becoming things, as is always the way of our organic lives.

That afternoon my wife Jean and I were talking in my room as I packed for a four-day retreat. I picked up the quilt, folded on a chair.

I sighed. “You know I’m not sure why I’ve kept this all this time. It’s been 25 years now. It’s been safe from moths in that plastic container, but stored in the bottom of the linen closet. And really I don’t know whose it is. I’ve always thought it may have been made by someone in my grandmother’s family. But I have no idea.”

My sisters and I had found the quilt after my mother died in 1998, after the last person on earth who could tell us its story was gone. Still, why would it be there, thrust into the back of her linen closet, worn and used and hand-made, except perhaps it had been quilted by someone in her female line? So I had packed it up and brought it back with me to California from my hometown of Washington, DC. My mother’s mother, my grandmother Carolyn, who was the only one of my grandparents not entirely Irish, had descended from Pennsylvania Methodists who may have gathered together of an afternoon for women and talk and laughter, and the useful healing movement of hands in a quilting bee, stitching layers of warmth and love for cold winter nights.

I had come upon the old quilt by chance just the day before, finally cleaning out the overstuffed closet. That evening I asked a friend, a master quilter and writer in one of my online writing groups, about the basket pattern. Was it special, historically significant? Should it be in a museum? Squinting at the quilt as I held it up before a 21st century screen, she deemed it a classic American design. And said, “What you should do with it is use it.”

Jean and I were just then re-thinking every single thing in the too-muchness of our house. It was time to clean things out, and we had to be stern, didn’t we? We had to be ready to give things away. It was easily possible that the quilt wasn’t special to our family at all, just a sturdy hand-me-down bought at a yard sale, something for me to pass along to someone who needed it.

Now I gazed at the quilt, wondering if it should remain with us. “I mean,” I said to Jean, “I’ve looked and looked, so many times. Nowhere has anyone signed it, or dated it, or left any message as to its origins.”

Jean suggested that we take that moment to look, really look. Not as I had for a signature, but at its artistry, at the tiny stitches, thousands upon thousands of them, and the precise quilting pattern in white thread, one stitch to another to another, on and on.

I looked at the fraying cloth of the solid blue edging of the quilt, and at a tiny, rusted safety pin, ancient and old, that was holding a part of it together.

“This was someone’s quilt,” I commented, “it was really used.”

Jean admired the fine quilting, its even texture and pattern, looking closely at one part of the fabric as she sat by the window in the late winter afternoon sun. Then I heard her voice like an echo in the air.

“Oh wait, what’s this?” And she read out:

“Sewed for Carrie Brace, 1897, Aunt Lillie”

Time inhaled a breath, and stopped for a moment. My heart leapt, hearing the name my grandmother Carolyn, my namesake, had been called much of her life—Carrie.

“What, what?” I called out, rushing to Jean’s side. She read it again, and we saw that sunlight had given us a portal into invisible history. The small words had been embroidered on creamy white cloth in cursive handwriting, in the same white thread as the rest of the quilt. It was close to invisible in ordinary light. But on that bright afternoon with our south-facing window, the sun low and streaming in, it was possible to see what had been hidden, what had always been there, waiting.

It all changed so quickly. The sun shifted, so did the part of the quilt in Jean’s hands when she put it down briefly. We had trouble finding the signature again even moments later. If the sun had been slightly different, if Jean had been holding a slightly different part of the quilt, if she had strolled into my room at a slightly different hour…

In truth, it didn’t have to happen, it never had to happen.

But it did, on an ordinary afternoon that was transported suddenly into wonder. And I thought, Grandmother, was it you who caught the day slyly, consigned as you had been to back shelves and history? Was it you who glinted the cloth and the sun into impossible alignment, so that the words stitched in pale white thread on white cloth could sing forth?

For now I know Grandma: this quilt in my hands was made for you, when you were nine years old. It was carefully stitched to keep you warm, giving you an embrace on cold Pennsylvania nights. It was your body resting under its sanctuary, your hands loving and re-loving the edges. It had been sewed by your aunt, my great-great-aunt Lillie, who had grown up along Lake Pleasant in Pennsylvania to become a master quilter in days that feel so long ago to us, but which were simply her present days, then.

Grandma, it was you resting under this quilt year after year as you came to teenagehood, and a new century, and business school for women, and running “Carrie’s General Store” in Waterford, Pennsylvania. You had it when you met my grandfather, a traveling Irishman in his fifties and you a businesswoman in your thirties, and you fell into a love match. It came with you when you traveled with him to the rest of your life in Florida, where my mother grew up. It was there when my mother met my father and moved to Washington, D.C., where you would move, too, finally in 1968, when you were widowed and I was ten. You lived there for the last decade of your life. Your quilt was stored in the linen closet outside your room on the second floor.

I wonder Grandma, did you know that I, your granddaughter, your namesake, your little friend who liked to visit your room, would be 65 before I understood? That this quilt was made by kerosene lamplight, your mother’s sister Lillie wearing a pair of thick, newfangled eyeglasses that helped the perfect stitches fall into place. That the day would come when I would hold up your gift, as my gift, as our gift, the past alive like sunlight and lamplight? As alive as my own mother’s hands as a girl, lying in bed in Florida in the 1920s under that same quilt. I can see Aunt Lillie’s hands bending down to touch my mother’s young cheek on their annual visits to Pennsylvania, as Lillie clasped my mother’s little hand, hand to hand. The same hands that held mine, changed me, birthed me, the same hands that put the quilt in the linen closet for me to find when the moment came.

And now I see all of them smiling down, the women of my mother’s mother’s line, looking at me as they shake their heads slightly, knowingly. I see them in their quilting bee, all the women smiling, nudging one another at my slowness. And I am smiling now too, and I am saying that it took a while, but I have finally seen, we have finally found each other. For I know this now: that history is a quilter named Lillie, satisfied that her art was complete, stitching her name so as to be present but invisible, like so much women’s history. She calmly offered the date, and the who and the why. Lillie as historian, as master artist, smiling at her accomplishment, the modest signature, her hands calm and sure, then later slow and arthritic, women’s hands, my hands, my very own hands.

And there was more. A month after our discovery last February 2023, I visited my sisters Pauline and Mary in Virginia for the first time since Covid, to finally see each other, to touch and embrace, hand to hand. We three could feel our origins, we giggly sisters in our attic bedrooms, now in our sixties and seventies. Pauline needed to get the boxes of our family things out of her basement, and we were the only ones who could look at it all and make decisions about what to keep and what to let go.

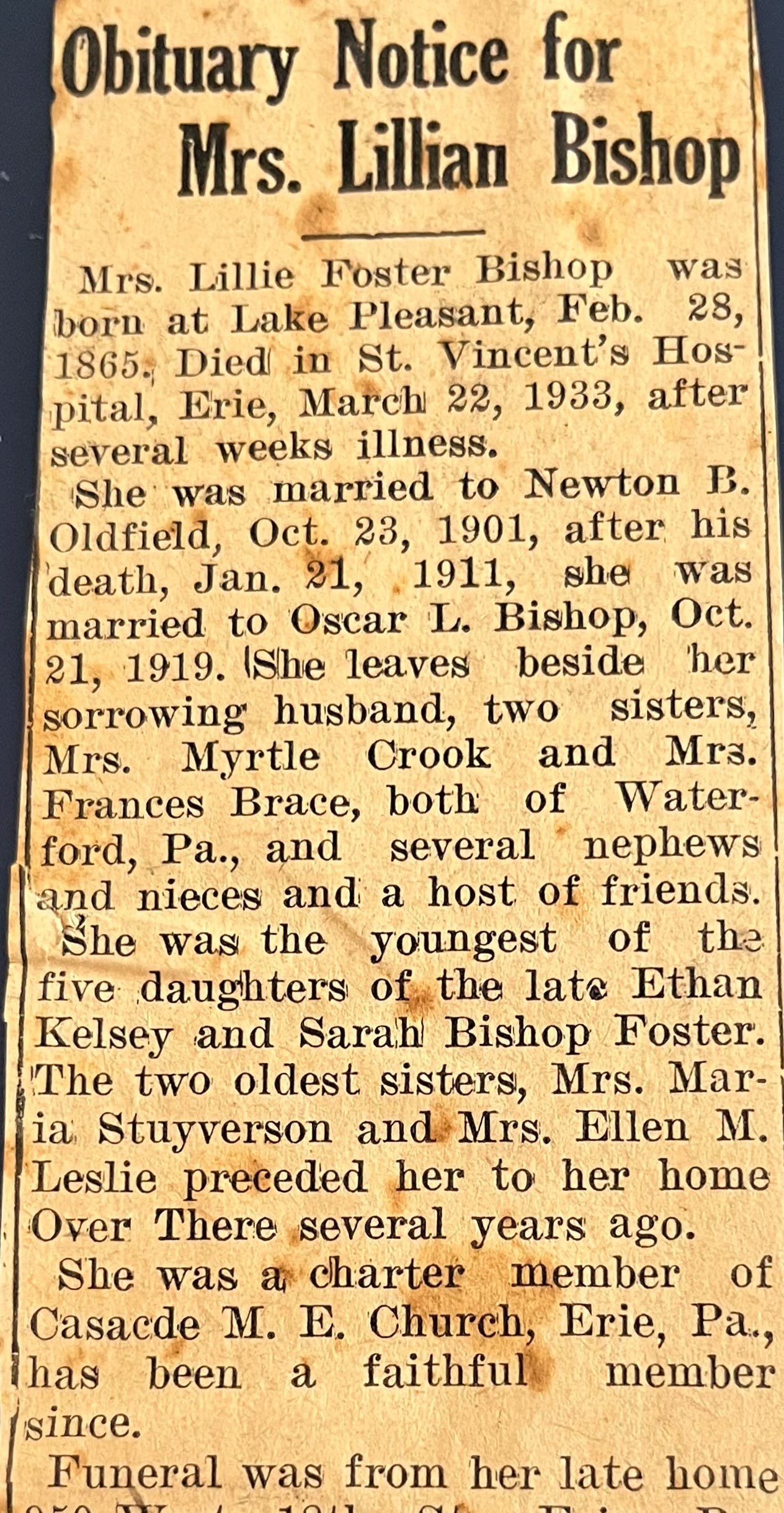

Among boxes and boxes of papers my grandmother Carolyn had kept, I came upon a large file of obituaries she had clipped from newspapers. There were several hundred of them. One by one I went through, knowing the gold that obituaries can provide, keeping every one that had a family name. I was focused on the endless sorting before us, but then in another sudden illumination there she was in browned and fragile newsprint, the newly unveiled maker of the quilt: “Obituary Notice for Mrs. Lillian Bishop.”

Aunt Lillie! I learned that she was the youngest of five daughters, that she was born in 1863 in upstate Pennsylvania during the Civil War. She married later in life, at 36, and married again after she was widowed ten years later. She never had children, but had “a host of friends” and a large family. And as I knew, she had a young niece named Carrie to reach out to with hand-made stitches of thread, cotton and love.

In the end, it is her quilt that remains. Beyond Lillie’s life, beyond Carrie's life, and my mother’s and mine, and the women of our female line who will inherit it. The quilt will live on past us, like an oak tree planted 150 years ago, or a necklace passed down again and again, or a cherished photograph, a knitted blanket, a painting, a postcard, a ring.

The other night a friend showed me the shelves she had just built to hold a lifetime of her collected stones and rocks. It was glorious. And it was one essence of her soul, and her deeper lineage. The material things each of us cherish and keep near echo who we are in ways that are sometimes deeper than anything we can say.

The quilt re-aligns my sight to what I know of history, the thing I always did know: that history is written in books but is alive in things, in us, in the stories we tell through time, in the things we keep and cherish and the things we pass down, and in our quiet inner knowings, like the urge to keep the quilt, which are in many ways our most essential compass.

The baskets sewn into my quilt that repeat again and again seem to tell a story: We are here, we are here, we are here. On nights when the world feels shaky I keep the quilt near so that my hands can touch it, thanking my grandmothers for reaching out, for returning themselves to the center of my life once more. They have given me a portal into remembrance, into gratitude, into dazzling synchronicity and thrilling sunlight, telling me that the world is magic.

In these times when existential meta-issues can paralyze us and monopolize our minds and attention, we can become lost. There are so many issues, and we all know them, and the list is long. We must pay attention to all this, yes, and we must take action. But like so many, I am often pulled into the vortex of the large and the insoluble to the detriment of paying attention to the small, the direct, the beautiful, and the doable. I lose everyday moments of synchronicity and astonishment, simply by not paying attention.

My quilt keeps me present. It says remember, it says look, it says embrace. It reminds me daily that our existence is large and vast, that our souls are wide and deep. That everywhere all around us are invisible stories waiting to be unveiled, that the ones who came before reach out to us, alive and speaking. They are with us. We can never be alone.

What will I fill the endless baskets of my quilt with? Wildflowers, blackberries, cotton balls, picnic lunches, balls of yarn, ginger muffins, fresh-picked apples, toys for my grandsons, letters to friends. I will fill them with books and journals and scarves and pens and candles. I will fill them with synchronicities, sightings, dreams, illuminations, with poems and prayers, with my broken heart and my embracing arms. And when I am done, I will say thank you Lillie. My basket is full.

Notes:

I learned through a bit of research that the design is a Colonial Basket Quilt which was popular in Pennsylvania in the 1880s.

Recommendations:

“I Am a Noise,” documentary film about Joan Baez, as few of us have ever seen her. Seeringly honest and truly extraordinary, and can be found online streaming.

“Hallelujah,” a film about the many versions and background of the famous song by Leonard Cohen. Thrilling and deeply moving. On Netflix.

“Turn Every Page,” a fascinating documentary about the working relationship between the writer Robert Caro and his editor Robert Gottlieb, online streaming.

“Stop Making Sense,” the classic 1984 concert film by the band Talking Heads, often called the best concert film of all time, has been re-mastered and re-released. I found it incredible, beautiful, rhythmic and mystifying. It was in theatres and is not on streaming yet, but keep an eye out.

On the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, like so many I continue to be heartbroken, knowing that so many beloved people in my life are grieving and anguished, both Palestinian and Jewish. I’ve been helped by writing & interviews with the famous scholar Edward Said and the podcast of the political thinker Ezra Klein (several episodes since Oct 18), as well as +972 Magazine, run by a group of Palestinian and Israeli journalists, recommended by Deena Metzger. To aid families currently in Gaza in the midst of daily bombing, you can donate to Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund. To call for an immediate ceasefire, you can take action here.

In Celebration of the Muse: It is fabulous news that the long-time Santa Cruz poetry series In Celebration of the Muse will be sponsored in 2024 by the amazing Santa Cruz Hive Poetry Collective. You can find the Hive’s excellent poetry podcast here. The Muse will be a live event on April 26, 6:30-8:30 pm at Cabrillo Horticulture. Submissions are being accepted and due February 1, 2024. You can submit here.

You are invited to share this essay and newsletter with those who would be interested.

“History is written in books but lives in things.” This was such a moving piece, Carolyn, a spiritual journey. I’m was struck silent and stilled by moment Jean found the signature, the sun in the right place, the moment waiting to be found again generations later. Just wow.

Beautiful Carolyn, the mystery of finding your through line. I can feel the moment Jean finds the invisible signature...I love -- history is written in books but lives in things. I am going through the house, so hard to let go of things that are not things, but stories and memories. Through lines. Love, Nora