Dear Friends,

Blessings to you in these late April days. In the midst of so much heartbreak, war and instability in the world, I see all around me that the Earth is simply herself, Spring arrives and our garden is a wild beauty.

Before I share my essay “Meeting Newgrange: Human Ingenuity and the Sun” about Ireland’s famous archeological monument and its solar alignment, I want to mention that I was very moved by the response to the announcement of my “Landscape of Soul and Story” Tour and Writing Retreat in Ireland this September. We have a remarkable group of writers, teachers, poets, thinkers and artists joining us! The trip is going to be amazing. There are only two spots left. If you are considering this journey, please let me know as soon as possible. You can find all the details here.

And.. thinking as I am of solar alignments, I also want to note that I was in Texas three weeks ago for the total solar eclipse—the moment when the Moon moves precisely between the Earth and the Sun, entirely blocking the Sun for a few moments before continuing on its orbit. On a clear day all sunlight leaves the sky; it turns dark; stars appear and glitter in daytime. In 2017, I experienced this at a total solar eclipse in Oregon, which I wrote about here. It was spectacular and soul-changing.

But on the morning of April 8 in Austin we had no idea what we would see, for clouds filled much of the Texas sky. The white silver river above us moved and billowed rather like the Irish sky throughout the 80 minutes leading up to totality. Here and there the clouds thinned, and we were able to watch through our eclipse glasses as the moon moved steadily through the gray sky to its rendezvous with the Sun, until eventually the Sun looked like a crescent moon. As we came close to totality, a gray dark descended. It turned cool.

Then—the clouds flowed and thinned just enough for us to see the stunning alignment. A perfect ring of fire, caused by wispy white streamers glowing from the Sun behind the dark Moon, hovered and shimmered in the silver sky. It was ethereal and gorgeous. Otherworldly.

Afterwards, a stillness filled us. We spoke in low tones. We were all more deeply within our own souls. I took out my notebook and jotted down a poem. We sat in companionable ease as the day re-emerged into itself. The light slowly returned, the air turned ordinary. After the totality, amazingly, the clouds barely parted again. The silver-wispy glory we’d been privileged to see in the sky could easily have never been visible to us.

It was not unlike in Ireland, where there are many ancient megalithic sites with solar orientations. These alignments are glorious, but the cloudy Irish skies must part enough for you to see them.

Years ago I fell in love with Ireland’s exquisite 5,000-year-old passage mound called Newgrange. Like many ancient monuments around the world, Newgrange is a testament to the fact that humans have been tracking the movements of the Sun and the cosmos for many millennia. Newgrange is a primary reason I began offering my Ireland tours and writing retreats in the first place.

The essay below is an edited excerpt from my forthcoming book about Ireland, The Light of Ordinary Days. May this offering bring you a moment of possibility and beauty.

Blessings and peace to you,

Carolyn

Meeting Newgrange: Human Ingenuity and the Sun

I can still remember the first time I saw an image of the ancient stone.

It was evening, March 1996, and my mother and I were waiting for our overnight flight to Ireland. We’d arrived at the airport hours early, and over dinner I picked up an Irish tour book. As we looked at iconic castles, pubs, cottages, monasteries and rivers, at one point a particular image stopped me quick. It was a tall, massive stone, laid sideways, covered with fluid carvings. One of the carvings was a large, magnificent triple spiral. I’d seen images of that stone, or something like it, before.

It was in Ireland? I squinted at the picture.

“Oh, that’s Newgrange,” my mother said. “You should see it sometime. Maybe you could go when you return to Ireland this summer. Your cousin Peggy lives nearby.”

Indeed that summer I did visit Peggy, who lives in Swords just north of Dublin. One morning we drove into the Boyne Valley, Peggy following road signs to Newgrange. When we came to a particular turn along a bend in the River Boyne, I don’t know what I expected—I was there simply to see the exquisite carved stone—but in no part of my mind could I have imagined the imposing white monument rising out of the land, situated on the highest point of a ridge.

Soon Peggy and I stood with a dozen other visitors before the huge white mound. It was large enough, we learned, to cover an acre. The white of the mound came from small white quartz stones which covered the front of the monument.

The magnificent entrance stone sat sideways at the opening. And it was huge. If I lay down beside it, I would only reach about two-thirds of its length. Even on its side it came up my waist. The designs were stunning—a large triple spiral covered half the stone in a famous motif which has now been reproduced all over Ireland.

In its presence for the first time, I felt a bit like a drunken sailor finally reaching port after a lifetime away. I wanted to call out or whoop at the stone’s beauty. Instead I stood quietly and did my best to drink in the presence of the stone and the intricate carvings.

We learned it was possible to go inside the mound, and suddenly the guide was preparing our small tour group to do just that.

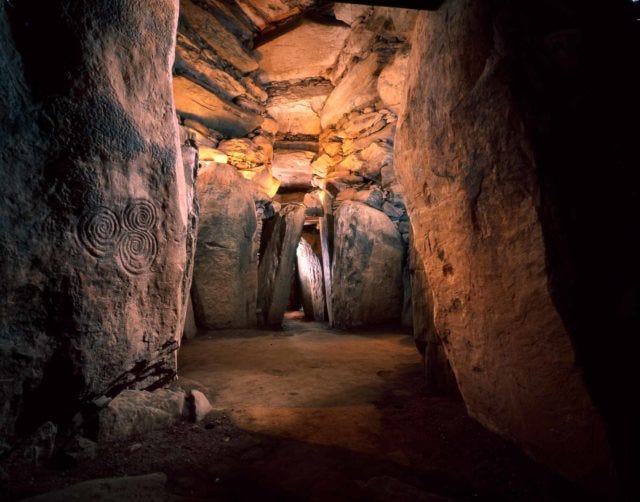

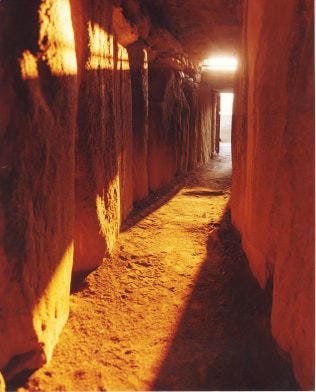

The passageway was narrow and a full sixty feet long, with space for one person at a time, lined on either side by megalithic standing stones. Each was about five or six feet tall, some with spirals and art carved into the surface. The guide asked that we be careful to protect the venerable old stones and not press against them.

Then we all began, one by one, to walk inside.

There are moments when time telescopes, and things shimmer unaccountably. As I walked through that narrow passage the first time, so intimately close to the tall stones, I felt touched by a strange light. The stones along the entrance seemed to softly hold us all up. I wanted to pause and greet each one, but it wasn’t possible; there was someone behind me, and it was only fair to keep moving. Then a few more steps, and I emerged into the tall inner chamber.

Inside: it was a church. My god, my Catholic-girl self said, eyes wide. The inner chamber was circular—about twenty feet in diameter—and made of elegant, solemn standing stones. The ceiling, built of huge stones laid in beveled rows, soared twenty feet above us. There were three recesses along the sides, like little chapels. The air was comfortable, dry, and a little cool.

Everywhere one looked were marvels of sacred art. An elegant triple spiral on the back stone, a heady profusion of decorated symbols, spirals, concentric circles, and chevrons had been carved into the granite. All around us the great standing stones stood in quiet antiquity. The air was pure and granite-scented. It was the mineral scent of earth itself. We were standing inside earth, in a human re-creation of our original source.

The guide paused. One of the more remarkable things about Newgrange, she said, was that it had been precisely engineered to receive the light of the rising sun on the winter solstice. Sunrise entered the long entranceway and filled the inner chamber for eighteen minutes.

“Would you like to see the light?” she asked. “Only a few people are able to experience the actual phenomenon each year on the winter solstice. But we can offer you a re-creation.”

And with that, she turned out the electric lights inside the mound.

Instantly we experienced the mound in its pure state. The darkness was total and complete. I had never experienced anything remotely like it.

My entire body relaxed. The darkness welled up around me like a thickness or awareness. I raised my hand to within an inch of my face, saw nothing, felt nothing but cool air. It was akin to a dark, sweet bath that offered respite. I wanted to lay down and curl up within it, rest and simply be.

But what happened next will be forever seared in my mind. A small pinhole of light began to make its way down the passageway, in a re-creation of sunlight slowly entering the mound. The small light, about the thickness of a pencil, made its way down the passage, grew in size, and then softly illuminated the chamber where we stood.

There were small grunts and gasps in the room, exclamations and deep breaths. The guide smiled. This was only a poor re-creation, she said. The actual event, which she had been privileged to see the previous December, was almost impossible to describe—the light was warmer, more golden; it all took longer, the chamber remained illuminated in sunlight for a full eighteen minutes before it slowly withdrew from the mound.

When it was time for our group to leave the inner chamber I really, really did not want to go. I stayed within to the very last moment.

Finally the guide gently urged me on. I knew I had been forever changed. Part of me understood that my destiny had been altered in that moment.

I learned that day that an Irish archeologist named Michael O’Kelly excavated Newgrange in the 1960s. Professor O’Kelly stunned the world, including himself, when new archeological carbon-dating methods showed that Newgrange was a thousand years older than anyone imagined. The predominant theory at the time was that it had been built around 2000 BCE, but the new analysis dated it to 3200 BCE. This meant that it was a thousand years older than Stonehenge in England and the Pyramids in Egypt.

Newgrange is in fact one of the oldest extant human-built structures in the world. This carbon dating made clear that it was built by the native Irish. During excavation, Professor O’Kelly repaired the passageway by returning tilted stones upright. He also discovered and repaired a rectangular opening above the entrance, which he called the “roof box.”

During his work, O’Kelly heard a persistent claim among the Irish locals that sunlight entered the mound at a particular time of year and lit up the triple spiral stone far inside the chamber. Some said this happened on the Winter Solstice, others the Summer Solstice. No one had seen it firsthand. At the time, the idea of a solar orientation for Newgrange was nonsensical to most archeologists. O’Kelly thought probably the locals were confusing it with the famous summer orientation at Stonehenge. But, seeing that the entrance faced toward the winter sunrise, he decided to investigate the claim.

On December 21, 1967, O’Kelly drove from his home in Cork to Newgrange in time for the sunrise at 9 am. “I was there entirely alone,” he said later in an interview. “When I came into the tomb I knew there was a possibility of seeing the sunrise because the sky had been clear…I was literally astounded… The light began as a thin pencil and widened to a band of about six inches. There was so much light reflected from the floor that I could walk around inside without a lamp and avoid bumping off the stones. It was so bright I could see the roof twenty feet above me…And then, after a few minutes, the shaft of light narrowed as the sun appeared to pass westward across the slit, and total darkness came once more.”

The sun entered, O’Kelly saw, not through the door opening, but through the roof box above the door. It was an ingenious design: as the land sloped slightly upward, the interior of the mound was precisely lined up with light entering at the entrance’s roofline. (You can see the roofbox in the first image of the Newgrange entrance stone above.)

Because the alignment was so unexpected—and so unlikely given archeological thinking at the time about the capacities of Neolithic people, not to mention of the native Irish—people actually wondered if the alignment could be accidental. O’Kelly hired an expert on archeological alignments who concluded that the solstice sun would have shone into the inner chamber 5,000 years ago when it was first built, and would probably do so forever.

Today this is obvious, and similar alignments have been found at many other megalithic sites in Ireland. Still, until my 1996 journey, I did not understand that the Irish landscape is filled with a profusion of ancient sites like Newgrange, many thousands of years old. Each of these places hold stories that have echoed back and forth between the land and the Irish people from endless time.

After my return from Ireland, when I told people about the stunning winter solstice alignment at Newgrange—the pinhole of light moving slowly through the passageway of standing stones and illuminating the inner chamber—they sighed and said they wanted to come with me the next time I went. It happened so often that I began to consider the idea. I remembered the ancient standing stone on Bere Island telling me to bring people to it. And after all, I’d seen my parents bring groups to Ireland time and again.

I organized my first tour and writing retreat in 2002 because I had a bone-deep urge to show the world (or at least a few people in my world) ancient sites like Newgrange and the other very sacred parts of my homeland—places that were so extraordinary, yet about which I had heard so little in my very Irish American life.

I could not have imagined then that these tours would become a rich mainstay of my life, not to mention all the ways that Ireland would provide a portal back to my own soul.

It feels deeply right that I will be returning soon. Newgrange and all of the ancient human-designed solar alignments all over the world remind us that we are part of a vast cosmos, and a story more mysterious and more beautiful than any of us can imagine.

You can find more information on my September Tour and Writing Retreat in Ireland here.

All images by the author except where noted.

There are dozens of books about Newgrange and Ireland’s neolithic heritage. For this essay, see Michael J. O’Kelly’s foundational monograph, Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend. The interview with Professor O’Kelly is from the book Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World.